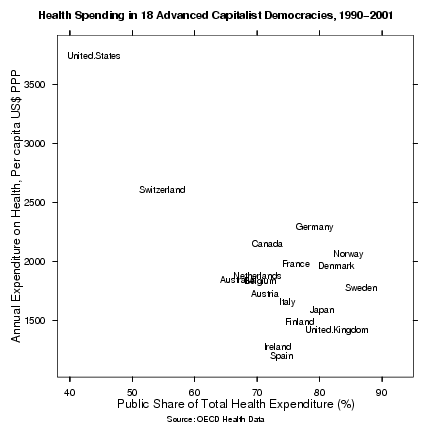

Brayden King notes that the “Wall Street Journal”:https://print.wsj.com/print-registration/docs/6gcaf.html is concerned about ever-rising health care costs in the United States. I’ve been looking at data on national health systems for a paper I’m trying to write. It turns out that there’s a lot less theoretical work done on comparative health systems than you might think, certainly in comparison to the huge literature on welfare state regimes. Here’s a figure showing the relationship between the “Publicness” of the health system and the amount spent on health care per person per year. Data points are each country’s mean score on these measures for the years 1990 to 2001.

*Update*: I’ve relabeled the x-axis to remove a misleading reference to ratios.

You can also get a “nicer PDF version”:http://www.kieranhealy.org/files/misc/health-ratios.pdf of this figure. As you can see, health care in other advanced capitalist democracies is typically twice as public and half as expensive as the United States.

You can also get a “nicer PDF version”:http://www.kieranhealy.org/files/misc/health-ratios.pdf of this figure. As you can see, health care in other advanced capitalist democracies is typically twice as public and half as expensive as the United States.

Now, this picture doesn’t resolve a whole bunch of arguments about the relative efficiency of public vs private care or the right kind of health system to have. (Brian discussed “some of these issues”:https://www.crookedtimber.org/archives/000852.html last year. There’s not much evidence that the quality of care in the U.S. is twice as good as everywhere else.) Things are also complicated — or made worse — by the fact that, despite not having a national health system, U.S. public expenditure on health in the 1990s was higher in GDP terms than in Ireland, Switzerland, Spain, Austria, Japan, Australia and Britain. But a picture like this makes it easy to see that mainstream debate about health care in the U.S. happens inside a self-contained bubble, and that one of its main conservative tropes — the inevitable expense of some kind of universal health care system — is wholly divorced from the data.

{ 79 comments }

Dylan 07.14.04 at 4:22 am

The US figures must be inflated to at least some extent by R&D costs, on which the rest of the world gets a free ride. Even if all “pure” research is chopped out, expensive experimental procedures available only here should cause a slight bump, and free market drug prices inflated by price controls elsewhere are going to account for a much bigger part of the discrepancy.

Shai 07.14.04 at 4:44 am

the echo chamber is already ahead of you on this one. it goes something like, public systems are only cheap and sustainable because the american system assumes most of the costs of drug discovery, medical research, technological advancement. QED impervious to your argument.

(no one’s going to bother so it’s a safe and happy place to be)

ArC 07.14.04 at 4:47 am

Yeah, it’s too bad the rest of the world doesn’t do any R&D of its own… Oy. I hate hearing that argument, particularly since comparative R&D spending is so rarely quantified, either in terms of spending or quality (that is, research on workalike drugs spent entirely to gain another patent, but to no patient benefit seems of less importance to me.)

For what it’s worth, it’s my understanding that crucial work on fighting SARS was performed in many countries including China, Canada, France, Holland, and Germany. For example. And a few years ago, the example of Tsongas’ surgery having been developed in Canada came up…

Shai 07.14.04 at 4:49 am

by the way, I wrote that before I saw dylan’s post.

Chris Lawrence 07.14.04 at 4:59 am

I think what you’re seeing is that the more economic power is concentrated on one entity, the more it can control per-capita costs; the flip side of that is that this control is essentially rationing. Give all the economic power to a single US HMO/PPO (Sherman aside) and I suspect you’d have the same result as giving it all to the NHS or provincial medicaid boards.

I’d be curious, though, what the graph would look like if you stripped out catastrophic care due to violent crime; patching up gunshot victims due to drug turf wars is (a) not cheap and (b) rarely paid for by the victim (or the perp, for that matter). Probably no data for that, alas.

q 07.14.04 at 5:22 am

I can’t help feeling that the devil is in the detail. What about a chart on the comparative cost of some healthcare examples:

a) Fixing a broken arm of a child,

b) 1 hour counselling,

c) “Nosejob”

d) Chorionic Villus Sampling (CVS),

e) Abortion,

f) Surgery for removal of benign stomach cancer,

g) 1 month care for person dying of lung cancer?

eudoxis 07.14.04 at 5:49 am

There’s certainly not a linear trend in that figure. If anything, expenditures seem to rise toward the higher end of the public/private ratio with a minimum around 0.7. And if the US is pulled out as an anomaly, there seems to be very little, if any, correlation. This figure tells us nothing about the relationship between expenditures and public/private expense ratios. Just for instance, in the US, 80% of the health care expenditures are used for the last 30 days of life. Is that a result of less public spending or is that a self-contained cultural bubble? A temporal dimension might give some insight.

h. e. baber 07.14.04 at 6:22 am

Is there anything comparing costs of the non-medical support services that figure in the health care system–clerks pushing paper, processing 100 different kinds of insurance forms, duplicated administrative structures for various HMOs, etc?

Kieran Healy 07.14.04 at 6:41 am

There’s certainly not a linear trend in that figure.

I didn’t say there was supposed to be.

If anything, expenditures seem to rise toward the higher end of the public/private ratio with a minimum around 0.7. And if the US is pulled out as an anomaly, there seems to be very little, if any, correlation.

Yes, the point of the post was that the U.S. is a giant anomaly. If you take out the U.S. and Switzerland, you get “this picture”:http://www.kieranhealy.org/files/misc/health-ratios-ussz.png (or pdf), which basically shows no relationship. (The line is a nonparametric regression estimate.)

eudoxis 07.14.04 at 7:26 am

The (conservative) claim that a universal health system adds costs seem dubious for a number of reasons, e.g. single payer efficiency, etc., however, the data in the figure don’t counter that claim precisely because they don’t show a relationship between expense and public/private ratio. That doesn’t mean there isn’t a causative relationship between expense and payer source.

Sebastian Holsclaw 07.14.04 at 7:35 am

I think the R&D difference/effective world subsidy on drug prices can certainly be a factor. I suspect a larger factor is lawsuits. Not just the cost of settling and defending lawsuits, but the very difficult task of protecting yourself as if you were going to be sued every single time you treat a patient. I’m not sure how to quantify it, but doctors in the U.S. spend a lot of time talking about how annoying it is to have to cover their asses every time they do anything.

Zak Catem 07.14.04 at 8:05 am

Almost all medical research in the US takes place in government funded institutions. In the specific case of the pharmaceutical industry, the major companies devote themselves solely to incremental improvements in existing chemicals for which they hold patents, rather than investing research dollars in developing riskier new drugs. Given that the taxpayer already bears most of the burden of providing funds for genuinely new medical research, it’s difficult to see how R&D costs have any bearing on the public/private health funding debate.

bad Jim 07.14.04 at 8:15 am

It’s not common knowledge in the U.S. that Canadians spend half as much on health care, nor that the average Dutch male is nearly 6’1″. Since the Brits have nearly the same problem with obesity, it might not be entirely beside the point to blame it on the unwillingness to use the metric system.

I’d rather blame it on soft drinks (pop or soda, if you’d rather). Fifty years ago, a Coke was a 6 oz bottle. Forty years ago, “Pepsi Cola hits the spot, twelve full ounces, that’s a lot.” These days twelve ounces are children’s portions, and adults get 16-64 oz.

Two liters of sugar water. Mmmm. Good and good for you, we doubt.

bad Jim 07.14.04 at 8:32 am

Here’s a link. At 183 cm, on my best day, I’m the tallest in my family. The chagrin of being below average in a country I’ve visited is as little to be borne as growing old (and damn the alternative!)

We Americans have the best everything. Our president has repeatedly asserted that we have the best health care in the world. We brook no dispute.

dsquared 07.14.04 at 8:53 am

I wouldn’t wager serious money on it, but I’d bet small amounts at reasonable odds that the cost figures in that chart don’t include any R&D-related costs. I base this educated guess on two facts; a) the UK looks much too low to have the entire research cost base of the UK biotech industry plus GlaxoSmithKline and b) I happen to know that the most commonly quoted headline series for the USA strips out research costs because I remember looking it up the last time I had an argument with someone on the internet.

Am I right, Kieran?

Jake McGuire 07.14.04 at 9:02 am

Of course the mainstream debate about health care in the US happens inside a self-contained bubble. It’s a domestic political issue – someone is going to have to tell the drug companies that they aren’t going to get what they’re asking for their latest and greatest drug, and someone is going to have to tell Americans that they’re not going to get the treatment they want because it’s too expensive for the benefit it gives, and that there’s no one they can sue to make it better.

These are all American domestic political concerns, and what the rest of the world does is possibly enlightening but of limited relevance in terms of actually getting things done here.

dsquared 07.14.04 at 9:04 am

Saving Mr Healy a job[1], I hereby confirm that I was right and win my bet. Kieran has used the “Expenditure on Health” series from the OECD Health Data, which does not include R&D. Research and development (along with food hygiene, hospices, cash benefits, education, etc, etc) is included in “Health-Related Items”, but that is not the series graphed here.

Perhaps you could put a small edit to this effect, KH, in order to forestall this particular talking point? Thank you so much. Then wash my car.

[1]”Mr Healy” is probably correctly referred to as “Dr Healy” or even “Professor Healy”, but we’re among friends here.

gavin 07.14.04 at 9:38 am

Although direct R&D costs are not included, purchases of pharmaceuticals are included. But it’s not possible to argue that US costs are higher because the US system is indirectly paying for all that R&D through higher pharmaceutical costs, since the US actually spends a smaller share of its total health bill on pharmaceuticals than Europe does (12.4% in 2001 vs 14.5% in Europe and an amazing 18.7% in Japan).

See page 4 of this presentation for those data: http://www.efpia.org/6_publ/infigure2004h.pdf

One small point in defence of the conservative trope: although universal public systems are often fairly cheap, it’s hard to see how the US could move towards such a system given its starting position. Such a move would imply a large reduction in the capital to labour ratio and the labour to output ratio in US healthcare, as well as a big contraction in the health insurance industry. It seems to me that the US system, while not delivering a significantly higher average level of health outcomes than Europe, does deliver a much higher level of average care – essentially, Americans are paying quite a lot for the consumption good aspects of healthcare (private, clean rooms, plump pillows, fruit baskets), not just the health outcome aspects. Of course, the inequality of outcomes is the issue that strikes most Europeans, but since I only get my evidence from watching ER, I don’t like to make too much of that!

So, I’m not sure that good policy makes good politics (or even practical politics) in this case. Nice chart though.

Keith M Ellis 07.14.04 at 10:26 am

Nope. There are some differences, though, and the insured Amerians are quite aware of them. I’d wager that a good portion of that difference is going to very costly procedures that are much more rare in other countries.

My favorite example of this involves my sister twelve years ago. We have a bone disease in my family. She had a problem with her ankle. Her ortho looked at x-rays, guessing there was a chip in there somewhere, but the x-rays were inconclusive. So he ordered an MRI. At the time, MRI machines were extraordinarily expensive, and the procedure cost, IIRC, about six-thousand dollars. The MRI showed a chip more clearly, and she had the arthroscopic surgery she would have had anyway. At that time, I know, Canada had two MRI in the entire country. The US had something like 150.

And, although I hate to agree with the conservatives on anything, I do think part of this has everything to do with malpractice and malpractice insurance. Doctors in the US have little choice but to consume all available medical resources or face the possibility of losing a lawsuit. Thus, a casual MRI.

Of the Americans who have health insurance (a shrinking majority), most still don’t face any sort of rationing and expect, as a right, access to any possible health care, regardless of cost. This includes extremely expensive pallative stuff in terminal illnesses, any kind of transplant (including heart transplants for people that will live, perhaps, only two years longer regardless). This is where a lot of that money is going. And the rest of it is going to waste and inefficiency because, frankly, even though private, this isn’t actually a functioning market. A functioning market, for example, wouldn’t allow Walgreens to sell fluoxetine at about %1000 that Costco sells it.

Jack 07.14.04 at 11:30 am

Why no bleating about America’s share of the pharmaceutical marketing costs? They are after all much larger than the R&D costs.

nick 07.14.04 at 12:39 pm

The US figures must be inflated to at least some extent by R&D costs, on which the rest of the world gets a free ride.

A myth exploded by Marcia Angell here:

And there is nothing peculiarly American about this industry. It is the very essence of a global enterprise. Roughly half of the largest drug companies are based in Europe. (The exact count shifts because of mergers.) In 2002, the top ten were the American companies Pfizer, Merck, Johnson & Johnson, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Wyeth (formerly American Home Products); the British companies GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca; the Swiss companies Novartis and Roche; and the French company Aventis (which in 2004 merged with another French company, Sanafi Synthelabo, putting it in third place). All are much alike in their operations. All price their drugs much higher here than in other markets.

Since the United States is the major profit center, it is simply good public relations for drug companies to pass themselves off as American, whether they are or not. It is true, however, that some of the European companies are now locating their R&D operations in the United States. They claim the reason for this is that we don’t regulate prices, as does much of the rest of the world. But more likely it is that they want to feed on the unparalleled research output of American universities and the NIH. In other words, it’s not private enterprise that draws them here but the very opposite—our publicly sponsored research enterprise.

That’s to say, American research is valuable primarily when it is not commercial. How much of Big Pharma’s research budgets go into ‘me too’ drugs and variants designed primarily to extend patent rights? More than is healthy, I’d warrant.

asg 07.14.04 at 1:48 pm

In my indirect experience (indirect since it is my father, not me, who has worked in medical research for the last 20+ years), the contention that no research goes on outside government-funded institutions is false. I don’t know about drug research, but virtually all the developments relating to, e.g., eyeglasses, contact lenses, wheelchairs, and other non-drug devices came out of the private sector. One should not conflate drug research with medical research in general.

Second, when my wife and I visited her childhood home in Nelson, British Columbia, there was a move underway by the government to close the only local hospital (which would have forced all hospital patients, including emergency ones, to drive 30-40 minutes to the hospital in Castlegar). This was widely protested but from what I heard around town it seemed inevitable. Obviously even in public systems hospitals must close, and perhaps that is even a sign of efficiency. And here in the U.S. we have hospitals and doctors closing up shop due to malpractice premiums. Perhaps this is just a sign that such things are inevitable regardless of what system you go with.

praktike 07.14.04 at 2:33 pm

It’s because we’re fat, isn’t it?

Jane Galt 07.14.04 at 2:56 pm

Of course if you simplify anyone’s argument dramatically enough, it looks foolish. No one sensible believes that it would be impossible to make American health care cost less; they simply believe that it would be impossible to make health care a) cost less and b) more accessible to a large number of people. If we bounce the over-eighty crowd out of the queue, cut down on “lifestyle” procedures like palliative surgery, severely limit payer/physician liability in order to reduce both insurance overhead and defensive medicine, implement long waiting times for non-life-threatening procedures, and accept that some possibly small number of people will die while waiting (the Fraser Institute found 192 in one year in Canada while waiting for heart surgery) while many others will suffer extra pain, refuse to pull out all the stops to get Grandma an extra six weeks of life, use the threat of “compulsory licensing” to force pharmaceutical companies to sell to the government at very near their marginal cost, sharply curtail the earning power of physicians, and jettison some of our private rooms in favour of open wards–well, certainly, we can make health care cheaper. We might even be able to cover all of the uninsured at lower total cost than we do now (although this is apparently complicated by the finding that some large percentage of those currently using emergency rooms for their primary care use said emergency rooms even when they have alternatives, such as free clinics). What free market advocates are disputing is the claim that through the magic of preventive care and administrative costs, the government can provide comparable coverage levels to what most Americans now have, for everyone, without an ever-increasing tax burden.

We also believe that, talk as you will of marketing costs, no industry can support an R&D effort on marginal cost pricing. The fact that pharmaceutical companies are located in Europe is irrelevant; everyone I know associated with the industry tells me that they expect to make the bulk of their economic profits in the US market. Our current policy privileges those who have diseases that are not currently pharmaceutically treatable, over those who have diseases that are. I’m not sure that reversing the priority is morally compelling, particularly when the effective term of non-marginal-cost pricing for most pharmaceuticals is under ten years. (though that’s growing slightly as the FDA gets faster approval procedures).

Is it worth it to spend all this money on short queues and heroic treatment of the very old and sick? On new drugs and the ability to sue for lavish compensation if something goes wrong? (What did that chap get when NHS amputated the wrong arm, and then had to go amputate the other? 10,000 pounds and an invitation to go on the dole?) Well, Americans appear to think it is, and have expressed that opinion at the ballot box. Culturally, we’re not very well disposed to having people in authority telling us what we can’t do; that alone is enough to slow any efforts towards nationalised health care.

Brian Weatherson 07.14.04 at 3:02 pm

As long as we’re comparing anecdotes about the quality of health-care in various countries, I’ve been much happier with the availability of services as an uninsured person in Australia than as an insured person in America. But then my health care needs are fairly minimal, so perhaps I’m not the best sample.

What always struck me about this graph was the position of Switzerland. Anyone who wants to explain away why America is such an outlier should, I think, show how the explanation generalises to Switzerland or come up with another explanation there. None of the explanations I’ve seen in this thread, or any other, seem to meet that desiderata.

Nicholas Weininger 07.14.04 at 3:43 pm

Drawing any single-issue conclusions from these sorts of “US as outlier” charts is always a suspect enterprise, because the US is an outlier in lots and lots of interrelated ways. I am reminded of the gun-rights debate, in which an eerily similar chart is often shown– the one where the US has much higher gun ownership rates and higher violent crime rates than other industrialized countries, but if you take out the US, the rest of the data show no correlation between gun ownership rates and crime rates.

The fact that we are an outlier in so many ways actually provides support to those who argue that a cost-efficient socialist health system in the US is near-impossible. We’re not (I’m not, anyway) claiming that it’s impossible *everywhere*, even though we might have other reasons to dislike health socialism independent of its cost. Rather, we claim that it would face unique and overwhelming difficulties in the US.

One of those difficulties, which other commenters have alluded to, is that too many Americans feel entitled to any care that might possibly help them, regardless of cost-benefit ratio. This results in a costly litigation problem related to, but distinct from, the malpractice problem: people will sue private insurers for refusing to cover treatments even if those treatments are experimental or of dubious effectiveness, so insurers’ ability to contain costs through sensible restrictions on what they cover is severely hampered.

A socialist health system in the US would do nothing to address this problem, and indeed would probably exacerbate it by removing the few remaining countervailing pressures of the marketplace.

Simon 07.14.04 at 3:50 pm

A quick note on “R&D” costs and this nonsense that we pay higher drug costs because of the R&D that goes into them.

I manage a segment of an R&D organization for a major US Pharma, and let me tell you, you’re not paying for the R&D. Average R&D expenditures among American Pharma and Medical Device companies are around 7% of our annual operating costs. Meanwhile, we spend somewhere around 50% of our annual operating costs on sales an marketing–that includes kickbacks to doctors for using our products.

So, my fellow Americans, you’re not paying for us to develop the drugs, you’re paying for us to sell them to you.

Thorley Winston 07.14.04 at 3:53 pm

Zak Catem wrote:

Really, evidence please.

According to the FDA, this only accounts for about 20% of Pharma’s R&D expenditures.

Source:

http://www.fda.gov/oc/speeches/2003/genericdrug0925.html

Even so, there are certainly benefits in improving existing drugs if it leads to more people being able to enjoy the health benefits of pharmaceuticals with lower dosages and/or fewer side effects that might not otherwise have been able to use them at all. Everything I’ve read on the subject also suggests that so-called “me-too†drugs have actually reduced the overall cost of pharmaceuticals to consumers.

Source:

http://www.drdonnica.com/news/00005065.htm

q 07.14.04 at 3:54 pm

Jane Galt: _Of course … … we’re not very well disposed to having people in authority telling us what we can’t do…._

How about we make the same argument for education? Abolish centrally-controlled education and taxes since it relies on a high level of interference in personal activity?

Thorley Winston 07.14.04 at 3:59 pm

Jack wrote:

Only if you include the cost of free sample pharmaceuticals which account for over half of the “marketing†costs. Otherwise the cost of marketing is less than the cost of R&D.

Source:

http://www.kff.org/rxdrugs/loader.cfm?url=/commonspot/security/getfile.cfm&PageID=13709

Thorley Winston 07.14.04 at 4:02 pm

Q wrote:

Seconded

Eddie Thomas 07.14.04 at 4:17 pm

Q: “How about we make the same argument for education? Abolish centrally-controlled education and taxes since it relies on a high level of interference in personal activity?”

I would rather have no public education than have only public education. As it is, I find our mixed system acceptable. The same is true of the field of medicine. There is no contradiction in supporting medical access for the poor and not wanting to be bound yourself to what the government decides is best for you.

taak 07.14.04 at 4:19 pm

Of course if you simplify anyone’s argument dramatically enough, it looks foolish.

You’re confusing an argument for a premise. The idea that public medicine is more expensive is a premise which is frequently used in other arguments, and this data appears to show that that premise is false. Nothing more complicated going on than that.

Now, earlier there were some sharing of anecdotal evidence, which as we all know has virtually no effect on empirical evidence. I would also like to suggest that hypotheticals are even less effective: this is form where it is taken that “there might be a problem” is taken to mean that there is. Well, when you clack off some hypotheticals in your head that you think are relevant, why should I put any weight to them?

Sebastian Holsclaw 07.14.04 at 4:33 pm

I would be curious to see what percentage of the total represent ‘heroic’ measures at the end of life that aren’t performed elsewhere.

(This is not an implication that the US is especially good for performing such ‘heroic’ measures. It seems quite possible that it would be best not to.)

And what a silly factoid that many pharma companies are owned by European companies. So what? They do a vast percentage of their work here, and they make a huge percentage of their profit here. Their European ownership is irrelavent to the issue of whether or not a socialized US market would significantly harm pharmaceutical research.

Zak Catem 07.14.04 at 4:34 pm

asg: As far as I know, publicly funded health systems outside the US don’t get better prices on medical equipment, just drugs. You can’t really argue that everyone else is getting a free ride on US wheelchair research. We pay the same prices you do.

Zak Catem 07.14.04 at 4:38 pm

Thorley Winston: There’s an article on this on the New York Review of Books website right now. Your final points are quite correct, but they do little to justify the claims of the industry re costs of research and free-riding foreigners.

Thorley Winston 07.14.04 at 4:48 pm

Zak Catem wrote:

Which book would that be? Please tell me it’s not the one by Marcia Angell which we already shredded over at Winds of Change for her blatant misrepresentation of the facts.

http://windsofchange.net/archives/005159.php#fn13

Zak Catem 07.14.04 at 5:28 pm

Good for you Thorley.

eudoxis 07.14.04 at 5:28 pm

Taak: You’re confusing an argument for a premise. The idea that public medicine is more expensive is a premise which is frequently used in other arguments, and this data appears to show that that premise is false.

These data don’t show a relationship between expenditure and public involvement. There is a real problem in showing no relationship between the two variables with a sample size of 18. There is insufficient information here to say that the “conservative trope” hypothesis is incorrect.

Back to the drawing board!

asg 07.14.04 at 5:28 pm

I really hope the CT trackback feature doesn’t have some kind of infinite loop. In any case…

How about we make the same argument for education? Abolish centrally-controlled education and taxes since it relies on a high level of interference in personal activity?

Sounds great!

As far as I know, publicly funded health systems outside the US don’t get better prices on medical equipment, just drugs. You can’t really argue that everyone else is getting a free ride on US wheelchair research.

I’m not arguing that anyone’s getting a free ride on wheelchair research (for all I know, the best wheelchairs were invented in Latvia). I am just arguing that drug research costs != medical research costs, and regardless of the former’s funding origins, the latter’s most certainly cannot be generalized as public sector. (I don’t believe your original assertion either, but I don’t have a cite like thorley winston’s.)

Nicholas Weininger 07.14.04 at 5:31 pm

taak: you’re mischaracterizing the premise to make it into a strawman. “Socialist medicine is always more expensive than non-socialist medicine” is not the premise. “All other things equal, socialist medicine is more expensive than non-socialist” is the premise.

And that premise is not falsified by the data shown, because there are a bunch of relevant other things that are not even remotely equal.

Thorley Winston 07.14.04 at 6:56 pm

As would I. I don’t have a cite for it but my understanding is that most health care costs are incurred in the last few years of life. In which case if in the United States we make greater efforts to preserve life in the last few years than these other nations, it could explain a considerable portion of the difference.

dsquared 07.14.04 at 7:08 pm

Anyone who wants to explain away why America is such an outlier should, I think, show how the explanation generalises to Switzerland or come up with another explanation there

Based on casual perusal of the inflight magazine of Swissair, Switzerland seems to be home to a quite extraordinary number of high-end plastic surgeons.

MQ 07.14.04 at 7:35 pm

Conservatives should not be allowed to claim on the basis of no evidence whatsoever that public care is more expensive than private. If they want to switch to the different argument that public care involves rationing, well, private care involves rationing too. And it will involve more and more rationing in the future. The question will always be who gets health care, how much, and how. For chairs or doughnuts, there are good reasons to believe that a system of purely private provision will address these questions most fairly and most efficiently. For health care, private provision is much more problematic, for lots of reasons. All countries, including the U.S., have mixed public/private provision. So we face an institutional design question. Mindlessly tossing out cliches about the free market (cheaper! innovative! profits good! government bad!) does not help. Not only are they often false when it comes to health care, the U.S. does not have a free market health care system and never will.

A U.S. public health care system will and should look different from European ones. For one thing we will spend much more, since we are richer. It will probably continue to have a large private sector role. My guess is that it will look like expanded Medicare, with private provision of new, expensive treatments that are not yet covered by the state system and are still at the left end of the learning curve.

MQ 07.14.04 at 7:40 pm

Another thing — a U.S. national health system will probably use market mechanisms (copays in particular) more extensively and effectively than other countries do. Using markets good; worshipping markets bad.

derPlau 07.14.04 at 8:20 pm

Am I missing something fundamental, or is the X-axis labelled incorrectly? Surely there’s not ~45 times more public spending than private spending on health in the US… Should this be “ratio of public to TOTAL spending”?

Tom 07.14.04 at 8:26 pm

“The US figures must be inflated to at least some extent by R&D costs, on which the rest of the world gets a free ride.”

Nah. Pharmaceutical costs were about 9% as a share of US health spending about 5 years ago. Even if they’re twice that now, the expense of pharma R&D can’t account for the discrepancy. Out-of-pocket costs for R&D for an approved drug run about $75 million. Depending on how you include failed drugs & basic research (and what discount factor you use), you come out with a cost of developing a new drug of $250-800 million. Around 30-40 new drugs are approved each year, so the is *no way* R&D expenditures on pharma can account for the ~$700 billion difference for the US spending 14% of GDP currently than if it spent 7% of GDP on healthcare (as in the UK).

(Most figures for R&D costs of a drug come out of some researchers at Tufts, who use the Weighted-Average Cost of Capital for the Phara Sector; however this gives an economic, not an accounting, cost for the Drug development (i.e. it includes an assumed profit rate).

“Only if you include the cost of free sample pharmaceuticals which account for over half of the “marketing†costs. Otherwise the cost of marketing is less than the cost of R&D.”

Thorley, gross margins on an on-patent small-molecule drugs are ~90%* . Marketing costs run ~30% in the pharma industry. So, if half of the marketing cost [in out-of-pocket costs] were samples (~15% of revenues), then the pharma company would be giving away one-and-a-half times as much drugs as free samples as it is selling. So, your assertion that half the cost is from free samples doesn’t make sense.

You’ll see in the Kaiser Foundation paper you reference that the cost of sample is shown as *retail* value; the actual out-of-pocket production cost to the pharma company is one-tenth of that. A bit of forsenic accounting is needed here.

(*I have no idea how the Kaiser Foundation got a cost of sales of ~25% – I remember going over several pharma 10-Ksm where the gross margins were 85-90% and comparing with biotech 10-Ks, and talking to biotechs who were concerned that their gross margins of only 80% were a source of strategic disadvantage relative to small-molecule pharma).

Jane Galt 07.14.04 at 8:26 pm

Simon — well, that’s not what your books say. Far be it from me to say that financial statements are always accurate, but looking at Pfizer’s financial statements I get R&D about 7 billion off operating expenses of approximately $31 billio, or a little less than 25%. I get SG&A of 50% of operating expenses, but of course marketing will only be a fraction of that number, and half of that marketing expense, if industry sources are to be believed, will be in the form of free samples, which can’t be realistically said to increase America’s health care spending. Merck and Glaxo seem to be in the same ballpark. Of course, they could be fudging, but they do have auditors. Is there another company I should be looking at?

Jane Galt 07.14.04 at 8:39 pm

Tom, that’s not necessarily a bizarre assumption: many people may sample drugs they don’t stay on after the trial period; many more may never be given out.

The way they’re accounted for is standard–in fact, I believe it’s required. Accounting for them at cost wouldn’t take into account lost revenue from giving your product away, and thus be a material misstatement. Executives would love to knock 50% off their sample costs if they could; they generally get paid in part based on their net income numbers. But the FASB wants them to be conservative. Of course, there is expected to be some eventual net benefit from lowering switching costs for users, but that’s accounted for elsewhere, when the revenue is realised.

Now, you’re correct that this does not present a perfectly true picture of the company’s marketing expenses. But we do not achieve perfection in this world. If pharmaceutical companies did not account for samples the way they do, activists would have a much lower number to throw around when they complain about marketing expenses. You can’t say “marketing expenses are around 30% of industry revenue”, implying that the number is outrageously high, and simultaneously complain that the

pharmas are overstating their marketing expense.

Bernard Yomtov 07.14.04 at 8:40 pm

Not that it changes much, but that ratio is an odd thing to chart isn’t it?

Why not just ratio of public to total? If you do that you see that the countries other than US and Switzerland are pretty tightly grouped in the 41-47% range, with the US under 30% and Switzerland around 35%.

Tom 07.14.04 at 8:44 pm

“You’ll see in the Kaiser Foundation paper you reference that the cost of sample is shown as retail value; the actual out-of-pocket production cost to the pharma company is one-tenth of that. ”

I’m trying to figure out why pharma companies might be booking the expense of free samples at retail cost. I suppose it might be tax-related, but I can’t believe the IRS would be that dumb as to fall for that. However, it would suggest that in terms of cashflow, pharma companies are even more profitable than their income statements would lead you to believe.

Detached Observer 07.14.04 at 8:48 pm

Some commenters on this post — like jane galt — seem to be arguing that that the US spends more on health care because its health care is of higher quality. They must have missed the link Kieran gives to an earlier Crooked Timber post demonstrating that this seems not to be the case.

Others — like thorley winston — end up arguing that the true reason is many US procedures are meant to prolong the life of old people and this accounts for the cost difference. But life expectancy in the US is significantly lower than life expectancy in western European democracies with socialized health care. Perhaps other factors are responsible for this — i.e. maybe Americans lead a more unhealthy lifestyle — but this kind of idle speculation is not an answer to the argument for nationalized health care made here.

As for higher drug prices in the US, they are very related to political corruption — Canada has lower drug prices because provinces have collective bargaining power and can drive down the cost of drugs. In the US, on the other hand, states cannot bargain with drug companies this way — courtesy of the political contributions made by pharmaceuticals.

Sebastian Holsclaw 07.14.04 at 9:26 pm

Wow detatched observer you dismiss as “idle speculation” the well known fact that Americans as a group don’t lead the healthiest lifestyle:

” i.e. maybe Americans lead a more unhealthy lifestyle — but this kind of idle speculation is not an answer to the argument for nationalized health care made here.”

and then come out with: “As for higher drug prices in the US, they are very related to political corruption — Canada has lower drug prices because provinces have collective bargaining power and can drive down the cost of drugs.”

You can perhaps argue that the higher cost of drugs in the US is not important to the discussion, but your explanation about why Canada has cheaper drug prices is flatly wrong. Canada insists on near marginal cost of drugs and threatens to break the patents of companies who do not comply. The main ‘collective bargaining power’ being utilized is the power of sovreign governments to ignore patents.

Quite simply, do you believe that the marginal cost of producing a pill can cover the cost of researching it? If not, it becomes quite clear that Canada is freeloading research costs. And if you believe that the marginal cost of pills can regularly cover billions in research costs, please state so clearly so we can analyze that presumption.

Jake McGuire 07.14.04 at 9:27 pm

Can we stop with the silly claim that Canada gets lower prices because they can buy in bulk and get a better deal that way? The big American insurance companies cover between a third and a half as many people as live in Canada, and have a very strong motive (profit!) to drive down supplier costs. If the lower prices were due to volume purchasing, these companies should be getting comparable deals, but they aren’t.

A much more plausible explanation is that the Canadian government can threaten “compulsory licensing” (i.e. “if we think you’re charging too much, we’ll just make it ourselves”).

The high cost of end-of-life care has nothing to do with life expectancy, by the way.

Finally, any measure of “quality of care” that does not explain who HMOs are very unpopular in the US is not going to be very useful in guiding US health care reform. Something to consider.

Tom 07.14.04 at 10:05 pm

“Quite simply, do you believe that the marginal cost of producing a pill can cover the cost of researching it? If not, it becomes quite clear that Canada is freeloading research costs.”

Sebastian, you’re abusing the concept of a marginal cost here; remember that a patented pharma drug is mostly an information product.

Selling drugs to Canada is an in-the-money option for a pharma company; therefore they will do so, and would do so so long as they get a contribution margin. If the variable costs of producing a drug are 10-15% of the US retail price, then a pharma company selling into the Canadian market is still getting ~70% gross margins. Additionally, they aren’t incurring the same marketing expenses in the more centralized Canadian market as with the more fragmented & complex US market.

Canadian drug consumers are no more “freeloading” that I am subscribing to my copy of the FT for .79 cents an issue when somebody buying it from a newsstand has to pay $1.50.

The US gets to pay more, and in return it has a larger share of the world pharma market, so influencing drug development profoundly; so we get lots of lifestyle drugs for expanding waistlines, depression & anxiety, and drooping phalli, and not so many anti-malaria drugs or new classes of antibiotics for infectious disease.

Jane Galt 07.14.04 at 11:33 pm

Tom, what Canada is doing is not quite what you suggest; it’s more like telling the FT that they’d better sell to you at 50% of the newsstand price, or else you’ll just steal the paper. I don’t see what resemblance this has to an option; it’s a simple case of price discrimination, only in the case of Canada, the government has set a price ceiling that makes such discrimination necessary. It’s particularly odd that you cite the lack of things like anti-malaria drugs, when one of the barriers to the development of such drugs is the (government induced) low level of appropriability in countries that need such drugs.

Nor is Sebastian “abusing” the concept of marginal cost; he’s using it absolutely correctly, as far as I can see. The problem of high fixed cost/low marginal cost industries with low appropriability leads itself to exactly the sort of behaviour we see in other governments: the temptation to force down prices below average cost is too strong to resist. If the US followed suit, I don’t see how one can conclude otherwise but that the pharmas would look a lot like generic companies, which is to say no significant R&D investment.

Pharmas are cash cows right now, as you can see by reading the balance sheets. But they’re ugly cash sucks during lean years, and somehow no one ever wants to make up their “excess losses”. Booking the cost of samples the way they do isn’t some anti-tax conspiracy Tom; I believe if you check, you’ll find that it is, in fact, required by the Financial Accounting Standards Board.

Detached observer, I’m taking issue with the statement that we spend more for nothing. Such comparisons tend to rely on two things: comparing health outcomes between large populations without controlling for many of the significant differences between them (particularly in the matter of collecting the statistics themselves–our infant mortality stats apparently suffer from our heroic prenatal interventions); and defining “good” outcomes very narrowly. Someone who suffers great pain, and the indignity of being housebound, for six or eighteen months while waiting for a hip replacement is inarguably getting worse healthcare than someone who waits two weeks and is back on their feet while their Canadian counterpart is still waiting for surgery. It doesn’t show up in mortality statistics, however, which is the most common metric used. Useless heroic end-of-life measures may not be better, but they’re highly in demand, and I find it hard to see where you’ll get the political support to curtail them. They want to be able to see their doctors whenever they want, instead of having to scheme and connive to get more than one checkup a year, as Canadians I’ve talked to do. Now, one could argue that morally, we should get rid of these features in order to provide more health care to those we currently feel are underserved–throw the very old and sick off the sled so the rest of us can survive. But one cannot pretend that this somehow amounts to superior healthcare for everyone. We will sacrifice, at the very least, the utility that consumers get out of things like doctor accessibility, ubiquitous private rooms, and so forth.

Kieran Healy 07.14.04 at 11:39 pm

Sorry, the x-axis should read “Public health expenditure as a percentage of total health expenditure.”

vernaculo 07.15.04 at 1:46 am

Health care seems to be impossible to argue about without assuming either the posture of a Martian insect, or that of a grieving mother.

The one dispassionate to a degree that’s no longer human, the other blinded by tears and the immediacy of suffering. There’s a balance somewhere, maybe.

In the US the givens, the assumptions, are:

1. That health care itself, meaning the constant extension of health care technique, is never going to be static, that it will lead at some magical point to the eradication of death itself.

The disgusting hubris at the base of that unspoken premise is what separates the insects from the mammals.

Death is not the enemy. Our genetic process needs the cleansing of death to work. We owe our abilities to the rebirth and succession of evolutionary struggle, whose penalties are non-reproduction; death being a guarantor of non-reproduction until recently. Why is it an unquestionable good to subvert the mechanisms that shaped us?

2. That what health care is is no more than another retailable service.

This is so absurd that its acceptance by the general populace seems to point directly to mass hypnosis.

Health care by definition is concerned with something so essential to human well-being that turning its management and providence over to capitalists is like turning a kindergarten over to cannibals.

MQ 07.15.04 at 2:16 am

One weird thing about debating drug costs with libertarian types is that they seem to be totally uninterested in how much subsidy we should be providing pharma companies with. All government-enforced monopoly protection good when it comes to drugs. What is the conception of “fair price” here? One cannot avoid this question because the free market cannot price drugs correctly without government interference. And one cannot say “fair price covers R&D cost” because it already does more than that. I teach my students that the proper pricing level for a regulated monopoly (which is what drug companies are!) leaves the monopoly with a return on capital roughly the same as the normal rate of return in the economy, so the owners of the regulated monopoly are not getting an extra reward over other capital owners. From the little I have seen it appears that drug company owners are making much more than the normal rate of profit. I do not know if that is correct but it seems to me that is where the debate should focus.

Jake McGuire 07.15.04 at 3:35 am

By your logic, should the government be involved in setting prices for movies? After all, Sony has a government-granted monopoly on Spider-Man 2…

Keith M Ellis 07.15.04 at 4:15 am

Funny you should mention that. As someone who is housebound, in great pain, needing two hip replacements (and at least a shoulder, too), with no health insurance (and no possibility of getting health insurance), the person who waits six or eighteen months for such procedures seems to me to be getting pretty good health care.

Robbo 07.15.04 at 4:58 am

I think it’s a combination of things. If you look at the chart, other than healthcare costs, several other things stand out against the USA.

1) As Sebastian Holsclaw said, I think A#1 is the lawsuit thing. In the USA, you order diagnostic tests to prove, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that your diagnosis is correct. Why? So a lawyer won’t shoot you down in court, and you’re left holding the $4Million bag. In Europe, compensation for patient injuries are generally geared to treating the injury (ie: no “jackpot” mentality) and are a “no fault” system (ie: find the error in the system, not “hang the lousy doctor”).

2) Americans ARE fat, and getting more fat all the time (the CDC statistics are listing more and more states where 25%+ (!) of the adults are obese–and predicts that with the current trend, it might be more than half of states in a decade that have 1/4 or more obese adults). But that’s in combination with…

3) America is much more racially diverse than any of the other countries listed. While some of it goes back to the fact that African Americans have been dealt a lousy hand and still, in many ways, are an underclass (and unfortunately, the statistics reflect it: AA’s are more likely to get heart attacks, diabetes, and a host of other problems, and do so at a younger age than whites). But ethnic homogenicity can be exploited both in terms of screening for diseases common to that genetic group and focusing treatments on diseases common in the ethnicity, and placing less cost emphasis on others (ie: Ireland doesn’t need to spend much on things like screening for thalassemia or sickle cell–which tend to be more common in Mediterranean and African gene pools). In fact, this would be supported by the fact that Canada is also high up there on expendatures, as is Germany (which has seen a large influx of central Asians in recent decades).

4) Plus, as others pointed out, Americans have disposable income to spend on health care. They spend more on petrol, more on entertainment, so… why not their health, too?

So, in sum, unless you transpose a European tort system on the USA (NOT likely if Edwards is elected to VP), change the consumer mentality of Americans, and can gain cost-efficiencies of ethnically homogeneous places like Ireland, you’re not likely to see European-style healthcare produce European-grade cost-efficiencies in the USA.

Detached Observer 07.15.04 at 7:53 am

jane,

I dont disagree that the statistics Brian Weatherson used to claim American health care does not appear better may be flawed. But do you have any evidence that this is the case, that America does provide better healthcare overall? Hitherto your claims have been anecdotal.

Rook 07.15.04 at 2:08 pm

It’s disgusting to think that people believe managed healthcare is worse then our set up. Pathetic.

JamesW 07.15.04 at 2:15 pm

Jane Galt:

” ….and jettison some of our private rooms in favour of open wards—well, certainly, we can make health care cheaper.”

I’ve lived in France for 31 years and none of my family have ever been hospitalised in, or even seen, an open ward. Baseline public health insurance gets you at worst a three-bed ward; anyone with complementary insurance (the whole middle class) gets a single room with TV and phone. No fruit baskets or fluffy pillows, though. Contrary to stereotype, the food is mostly awful. Wine is theoretically banned but I’ve found considerable tolerance.

Jane Galt 07.15.04 at 2:19 pm

Detached observer: Better is a relative, not an absolute. The British system is better if the metric is percentage of population covered; the US is better if the metric is satisfaction of those covered. Scare anecdotes aside, from what I’ve seen, while the majority of Americans are worried about not getting good coverage, a large majority are also very satisfied with the coverage they’ve so far received. People from other countries travel to the US to get healthcare, not the other way around.

MQ, the pharma industry does not seem to me, as a whole, to be earning economic rents. P/E’s in the industry seem to be between 13 and 15, which is downright modest by today’s standards, with returns in the 5-8% range. Of course, I’ve hardly done an exhaustive study, and if anyone has data showing much higher returns, I’d be interested to see it.

q 07.15.04 at 4:06 pm

It seems like we have 3 different “Public vs Private” debates here and people are talking at cross-purposes :-

1) Efficiency of healthcare provision

2) Quality of healthcare provision

3) Justice of healthcare provision

Of course, maybe the “just” solution is the one that provides the greatest quality at the lowest cost?

Jonathan Goldberg 07.15.04 at 6:38 pm

The effect of malpractice suits on health care has been mentioned by serveral posters. I’d like to point out that government-provided health care is of itself an anti-malpractice-suit measure. This is so because the cost of the extra health care made necessary by the bad effects of the malpractice are taken off the table, resulting in lowered incentives for such suits.

Sebastian Holsclaw 07.15.04 at 8:41 pm

The costs of additional health care are rarely the biggest-ticket item in malpractice suits. It is the pain-and-suffering damages that blow the top off of things.

Detached Observer 07.15.04 at 10:42 pm

jane galt wrote: “The British system is better if the metric is percentage of population covered; the US is better if the metric is satisfaction of those covered”

Wrong!

See the paper linked to by Brian Weatherson in a subsequent Crooked Timber post.

I quote: “The US was comparatively low [on satisfaction] also, with only 40 percent of people who were satisfied with their health care system. Even the United Kingdom, which has had persisting problems with its national health service in recent years had almost 60 percent of its people saying they were either very satisfied or fairly satisfied. ”

Jane Galt 07.15.04 at 11:53 pm

Detached observer, the commonly cited figure for numbers of privately insured Americans satisfied with their insurance is around 85%. A gross figure for America will include the 45% of health spending already done by the government, through Medicare and Medicaid. Unless you disaggregate private v. public (and charitable) spending, all you may be telling us is that Americans don’t like what you’re trying to give us more of. The Economist’s health care survey this week says only 20% of Canadians are satisfied with their system . . .

Detached Observer 07.16.04 at 5:37 am

jane,

So then you give up the claim that the US system is better if the metric is the satisfaction of those covered?

Now you are making a weaker claim — that privately insured Americans are more satisfied with their health care than Europeans.

That may very well be so — but does it really make the US health care system better? If, on average, Americans are less happy than Europeans but nevertheless a subgroup of Americans — a subgroup where, incidentally, membership correlates with income — is actually happier — that sounds like a system that is not only worse in absolute terms but also vastly more unequal.

As for the other argument you make — people report a higher rate of satisfaction with private insurers therefore public health care is bad — private insurers spend vastly more per person than medicare/medicaid do (see these slides for data). The point Kieran makes here is that if we had a system of public health care in which spent exactly as much as we do today — not less — we would most likely be better off.

Jane Galt 07.16.04 at 1:09 pm

The point, DO, is that advocates of public health care insinuate that everyone will be able to have the same quality health care they now enjoy, which is not true. Some people will be better off, while others — those who currently have coverage, and those with diseases that are not currently treatable by drugs, but which might be treated by drugs in the future — will be worse off. Consider that, whatever your opinion about the pharmaceutical industry’s marketing costs, research cannot be sustained at the marginal-cost pricing now found in every major market except America. If drug research stops, literally everyone in the world suffers. Which group — the larger number of future sick or the smaller number of current sick– have more moral claim on us?

q 07.16.04 at 1:50 pm

Jane Galt = _If drug research stops, literally everyone in the world suffers._

I am in the world!

I’ll die in about 50 years.

Drug research stopping now would not make me suffer. (If it hurts too much maybe I’ll push up the dial on the morphine drip.)

Therefore, if drug research stops not everyone in the world will suffer.

Those who will suffer:

-drug researchers

Various branches of the Christian Churches have open positions for missionaries who want to save the world, which drug investors and researchers are welcome to join.

Tom 07.16.04 at 8:12 pm

“MQ, the pharma industry does not seem to me, as a whole, to be earning economic rents. P/E’s in the industry seem to be between 13 and 15, which is downright modest by today’s standards, with returns in the 5-8% range.”

Tut tut, Jane. You can’t determine whether an industry’s gaining economic rents by P/E ratios; the rents would be priced into the current share price. Tobin’s Q would be a better bet.

I think there’s also been work done on why Biotech VC funds tend to get crappy returns (15-20%); the thesis being that small biotech start-ups are unable at acquisition to capture all of the value they create, because of financing constraints and the barrier-to-entry of replicating a big pharma company’s sales-and-distribution network.

“Of course, I’ve hardly done an exhaustive study, and if anyone has data showing much higher returns, I’d be interested to see it.”

I seem to recall a study (by Myers or Howe at MIT?) that sugggested that pharma was getting a return of ~2% above what the riskiness of the cashflows would warrant.

“Booking the cost of samples the way they do isn’t some anti-tax conspiracy Tom; I believe if you check, you’ll find that it is, in fact, required by the Financial Accounting Standards Board.”

Sorry, didn’t see your earlier post. And I caught the idea that it would diminish the marketing costs. However, it does suggest that the positive cashflows (given that the out-of-pocket marketing costs to the pharma company of the booked marketing expenses are higher than the FASB-standard reported earnings.

“Nor is Sebastian “abusing†the concept of marginal cost;”

Yes, he was; the governments aren’t forcing pharma companies to sell at below COGS, or the short-term marginal cost of the drug. So, selling into other markets offsets the R&D (and GA&S) overhead that development of drugs incur.

“he’s using it absolutely correctly, as far as I can see.”

I don’t think he showed that the prices given in gubmint-controlled *are* marginal costs; neither have you, for that matter. If the pharma companies are using the estimates of development costs coming out of Tufts, frex, then their profit is already priced into into the discount factor used for investment.

“The problem of high fixed cost/low marginal cost industries with low appropriability leads itself to exactly the sort of behaviour we see in other governments:”

OK. How about a mandatory auction of 1-2 additional licenses after, say, 4-5 years of drug introduction? No price controls, but would reduce monopoly profits from the patented position. Might be subject to challenge based on the consititutional right to patent (in the main text of the constitution, not in those amendment afterthoughts), but would certainly be OK for drugs developed using Bayh-Dole Act licenses.

(*This might not be entirely successful at competition, given that companies such as Roche have been caught price-fixing in food additives, so 2-3 licenses

Certainly for compounds created from Bayh-Dole

“the temptation to force down prices below average cost is too strong to resist. If the US followed suit, I don’t see how one can conclude otherwise but that the pharmas would look a lot like generic companies, which is to say no significant R&D investment.”

You and I have been around this one before. The argument I’ve made before is that the R&D we’d lose is that of marginal benefit, and that the high margins on patented drugs create incentives to spend large marketing $$; it’s a safer bet to spend more money on marketing to boost sales than to perform new development. If the US gubmint were to reduce the benefit of monopoly protection of drugs (by e.g. reducing extensions of patent life currently given, or having mandatory auctions of licenses after a given period of monopoly protection), then we’d see less me-too drugs based on the same mechanism, and less marketing $$.

(*Because physicans are slow to change drugs they perscribe, there’s a strong incentive to saturate marketing at the introduction of a drug ; ZS Associates, a pharma market consulting firm, have built a nice business based on this insight).

Detached Observer 07.17.04 at 2:45 am

jane,

I don’t know any “advocates of public health care” who “insinuate that everyone will be able to have the same quality health care they now enjoy.” Maybe they exist but certainly none of them post on crooked timber.

I’ll be the first to admit it — bill gates would most likely lose out if we introduced public health care.

The point being made here is that western European democracies have better average care at lower average cost per patient.

Robbo 07.17.04 at 4:36 am

Jonathan Goldberg wrote:

^”The effect of malpractice suits on health care has been mentioned by serveral posters. I’d like to point out that government-provided health care is of itself an anti-malpractice-suit measure. This is so because the cost of the extra health care made necessary by the bad effects of the malpractice are taken off the table, resulting in lowered incentives for such suits.”^

as Sebastian Holsclaw wrote, this isn’t likely to make a dent; in states where there isn’t a cap on malpractice damages, the usual malpractice settlement is about 70% “pain and suffering,” loss of consortium and other “soft” reasons, 20% things like lost wages and the like, and 10% future medical care. The future medical care % does go up for injuries to infants, but then so does the total suit (as high as $63MILLION, for one kid, that I’ve seen published); and the future medical care component actually disappears (for obvious reasons) for suits where the the alleged malpratice is for a “wrongful death.”

IMO, to talk about cost controls in medicine in the USA apart from *sweeping* tort reform is just foolishness. It’s not *just* that things like defending litigation and the cost to hospitals and physicians and the like for liability insurance drive up the overhead for providing care (one part of every claim that medicare pays goes *specifically* to pay for the malpractice overhead–and that component is indexed to the cost of malpractice insurance for that state… so we *all* pay for runaway malpractice costs, even if we *never* see a doctor, by paying taxes!). [Don’t believe me? Go over to http://www.cms.gov and look up “relative value units”–of course, trying to read the stuff can cure the most hopeless insomniac!] IMO, however, those “direct” costs are probably actually *dwarfed* by the cost of testing that malpractice-phobia drives.

But, in fairness to doctors, the other side of the coin is the *expectations* of patients that drive this litigation craziness. Americans basically expect an error-free medical system; one missed fatal heart attack, and the doctor is suddenly on the front page of the local paper and opening a subpenia from a lawyer, and praying his kids still get to go to college. One ER doc I know admits to me that probably 2/3 or more of the people he orders CAT scans on for their headaches are because he “has to” based upon the voiced complaint of the patient, even when his exam and instincts tell him otherwise. Why? Because *no* doctor (or human) is omniscient, and *no* doctor, no matter how talented and consiencious, is going to pick up every bad diagnosis from their physical exam (and even with a few cheap tests thrown in). And if that 40 year old mother of three who tells him she’s having the “worst headache of my life” (as she sits there and watches Jerry Springer and munches on Dorritos and screams at her kids) turns out to the be the one in a million who actually has bleeding in her brain–and if he misses it–the late woman’s estate will likely be contacting a personal injury lawyer to “get what they deserve” (plus a “little extra” for the hardworking attorney), and my friend will be making an appearance at a courtroom near you…

If my friend worked in western Europe, he’d likely just have to fill out some paperwork (because of all the beaurocracy involved). If he worked in the thrid world, the family would likely come back and thank him for doing the best he could…

So the question is, what type of expectations does the culture have? My impression is that western Europe, they tolerate the inevitable misses that occur, even when the outcome is bag, so long as the doctor showed due dilgence and followed correct procedure. In the third world, most people are just happy to have someone show up and hold their hand and give them a pill. In the USA, basically ANY bad outcome (in the minds of most) is a reason to lynch a doctor who “obviously didn’t do his job.” In short, Americans expect their doctors to be gods (but subservient gods, who do their whim) who are inerrant. The problem is from moving from a few errors (the errors inherent in a human doing their best in a “cost efficient” manner) to an “error free” system drives up the costs exponentially. Why? The “best effort” system makes sure the doctor orders tests that seem logical; the “error free” system forces the doctor exhaustively exclude every potential diagnosis known to man. Why? Because if they don’t, invariably some “Monday Morning Quarterback” type attorney is going to tell a jury a sad story of a patient who had something bad happen, and then turn to the doctor on the witness stand and say “Gee, doctor, didn’t you realize that Mr. X’s [fill in symptom] could have been [fill in catastrophic disease] and that by merely obtaining [fill in test costing $1000], you could have saved this person’s [life, limb, whatever]?”

Robbo 07.17.04 at 4:47 am

Also: before someone launches “Well, there must be more lousy doctors in America than other countries if there’s more suits in America” logic, it just doesn’t hold.

A well designed study by Harvard medical school sampled well-regarded specialists in their field about a variety of actual cases. They provided the “experts” everything that was available to the experts in the case and to the jurors.

The experts agreed with the jurors barely 50% of the time. The biggest predictor of cases that the jury thought constituted “malpractice” that the experts thought represented quality care with an unfortunate outcome? How “sad” the case was… ie: a baby that died despite the best available care often brought their parents a post-humus multimillion dollar “windfall.” Old winos who got slipshod care in a public hospital got nothing.

Robbo 07.17.04 at 4:54 am

Detached Observer wrote:

“I’ll be the first to admit it — bill gates would most likely lose out if we introduced public health care.”

Actually, that’s likely untrue. Unless you made it illegal to seek care from another country, the Bill Gates’s and Martha Stewarts of the world would merely jet to some other country to get what they wanted. So unless the *entire* developed world started rationing health care, it would create a “superclass” of patients wealthy enough to jet to Japan (or some such place) to get the surgery, test or whatever they desired.

Alternatively, unless participation in the “nationalized” system was compulsory for physicians, you’d invariably have doctors working on the side, taking cash only. Again, only the super wealthy would benefit.

Comments on this entry are closed.